Monkey See. Monkey Do.

It’s Not Just Trump

Monkey See. Monkey Do. It’s Not Just Trump

My daughters, Amber and Celeste, as children were not allowed to have stuffed animal monkeys as children.

As a Black mother that decision didn’t come from whimsy or overreaction. It came from history. From trauma. From lived experience. This is usually the moment when a well-meaning white person leans in to tell me I’m being “too sensitive” or “going overboard.” But sensitivity is not the issue.

Memory is.

When I was a student at Woodmont High School, standing in the cafeteria line, a white boy cut in front of me and called me a monkey. I caught my brother Errick’s eye across the room—my big brother was muscle-bound, on the football team—and I silently mouthed what the boy had said. Errick walked over, took off his black leather jacket, and cold-cocked him. The boy never returned to Woodmont. I think he was sent to private school.

I had protectors. Not everyone did.

It was like the time a white friend invited me and two other Black friends to her church in Honea Path. We were honor-roll students. The church wrote to the dean to report that they did not want “troublemakers” attending their services.

College Education From A Baptist Church in Honea Path, South Carolina, 1985 Dear Dean, Please ask your Black students not to return to our congregation. They are troublemakers breaking up our church by attending. This letter drizzled with Please & Thank You.' Finished off with: Sincerely Yours, Signed in Christian love. by the Minister-in-Charge

When I was a student at Texas Tech, a cartoon appeared in a school newsletter depicting Black people as apes. I wrote to the editor in protest. I was young, far from home, in Lubbock, Texas—but I did not lose my footing. I knew who I was. I knew where I came from. And I knew exactly what I was seeing.

It was like the cheerleading pool party where the Black cheerleaders were suddenly uninvited—because parents did not want their water “tainted.”

The Marsh Glenis Redmond Black campers are asked to leave the Valley Swim Club. It was said by one of the members that they “change the complexion of the pool.” Philadelphia, 2009 The day felt like a swamp full with the muck of it. There are some days that hold you thick, so intense you think, I’ll never forget this. But here I am now wondering what wing I was in. Was it “B” or “C”? Was I on my way to Algebra II or lunch, when I caught word that the invitation had been pulled back for the pool party? Not jerked from us all, just the black cheerleaders. The family didn’t want their water tainted. The words punched like a full-on jab. How does a 15-year-old brace the heart? The first instinct is to strike out like a cobra, fill the air with righteous rain. I can’t remember now, but somehow I found my school spirit by Friday, pumped all the pep I had into the rally, but the blue and white had begun to fade. That swimming pool memory is not so crisp but the swamp always creeps back into my mind. I just wanted what all kids want in the heat of July, turquoise blue waters unwavering and floating holding me firm above the fray. Published in What My Hand Say, 2018 The list goes on—too numerous to count. Most Black people I know are living with this kind of accumulated trauma, whether they name it or not. I once had a white friend I confided in, telling her about these moments. Her reflexive response was always the same: It’s not about race. It’s about class. Every time, she gaslit me. Eventually, I stopped confiding in her. Today, we are no longer friends. To be in my circle, you have to be willing to see—not just through the lens of your own privilege. I grew up in the 1960s and 70s surrounded by minstrel imagery—advertisements, television shows, comedy routines steeped in Blackface. Here is a poem I wrote about encountering such hateful depictions.

I was thirteen when I spied the billboard. These depictions were normalized. Much of white America saw nothing wrong with them. They laughed. Many still do. People often try to separate themselves from Trump, insisting they are “not like him,” not racist, not cruel. But wherever I have lived, these remarks—these ideas—have followed me. They are not anomalies. They are patterns. You Know You Are Not From Here Glenis Redmond when your dad retires and announces, we’re going home when South Carolina is just a concept not a place when it would never dawn on your parent’s to preview or set the context for the South when they just load all five of you into that 1974 puce green Chevy Nova and head south on I-95 when you are eyes-wide and full of questions when you see Sambo depicted on a roadside billboard when you do not understand the color lines at basketball games or on Sunday mornings, but then you wake to charred and smoldering grass from a cross burned in your neighborhood when you see a plantation for the first time and you are not awed by its beauty but haunted by the history not told on public tours when you learn to navigate the historical land mines when your steps become fluid dance moves in the margins and your tongue follows with fluent code switch and switch backs criks, hollers and down yonders when you do not know the word kin, but when you been here long enough you feel how blood circles back to here when you understand Dorothy’s double-edged decree There’s no place like home. There’s no place like home. The Listening Skin, 2022

I have heard these comments frequently:

Casual, dismissive remarks about Africa

“Aren’t you glad your people were enslaved? It saved you from a savage continent.”

Assertions that all Black women look like monkeys or too masculine.

Insults about our hair—its texture and its presence,

The belief that we are tainted, that our bodies somehow sully—leading to exclusion from pools and homes.

The white practice of naming pets after Black people, fully aware of the long history of equating Blackness with animality. For me, it is too soon. It has always been too soon.

This is not about one man.

It is not just Trump.

It is about subtle, corrosive racism—the microaggressions that accumulate, that seep into conversation, policy, culture, and self-perception. They bleed. They stain. They do their damage quietly, persistently.

So no, this is not oversensitivity.

This is vigilance.

This is memory doing its job.

This is a mother protecting her children.

You can deflect and say it’s “just him.”

I can’t even count how many times I’ve been called a monkey.

How many of my friends have been called it too. I can tell you one time is too many.

So, I ask:

In an era where a president can circulate imagery depicting the Obamas as monkeys—a trope rooted in centuries of dehumanization—what are you doing?

Are you calling it out?

Naming it for what it is?

Or explaining it away as politics, humor, or “not that deep”?

Because silence is a choice.

And history keeps a careful record of who spoke—and who didn’t.

Be vigilant. Speak up and out.

No matter the affront, I love in the face of hate how Black people are bent on Blooming Anyhow!

In the face of hatred, this is why we had to create affirmations like Say it loud. I am Black and I am proud. It is also why I felt compelled to embrace the West African tradition of praise poetry. These declarations were never about ego—they were about survival. When the world insisted on distortion, praise became a way to tell the truth out loud, to name ourselves fully, and to remember that our worth did not begin with resistance, but with lineage.

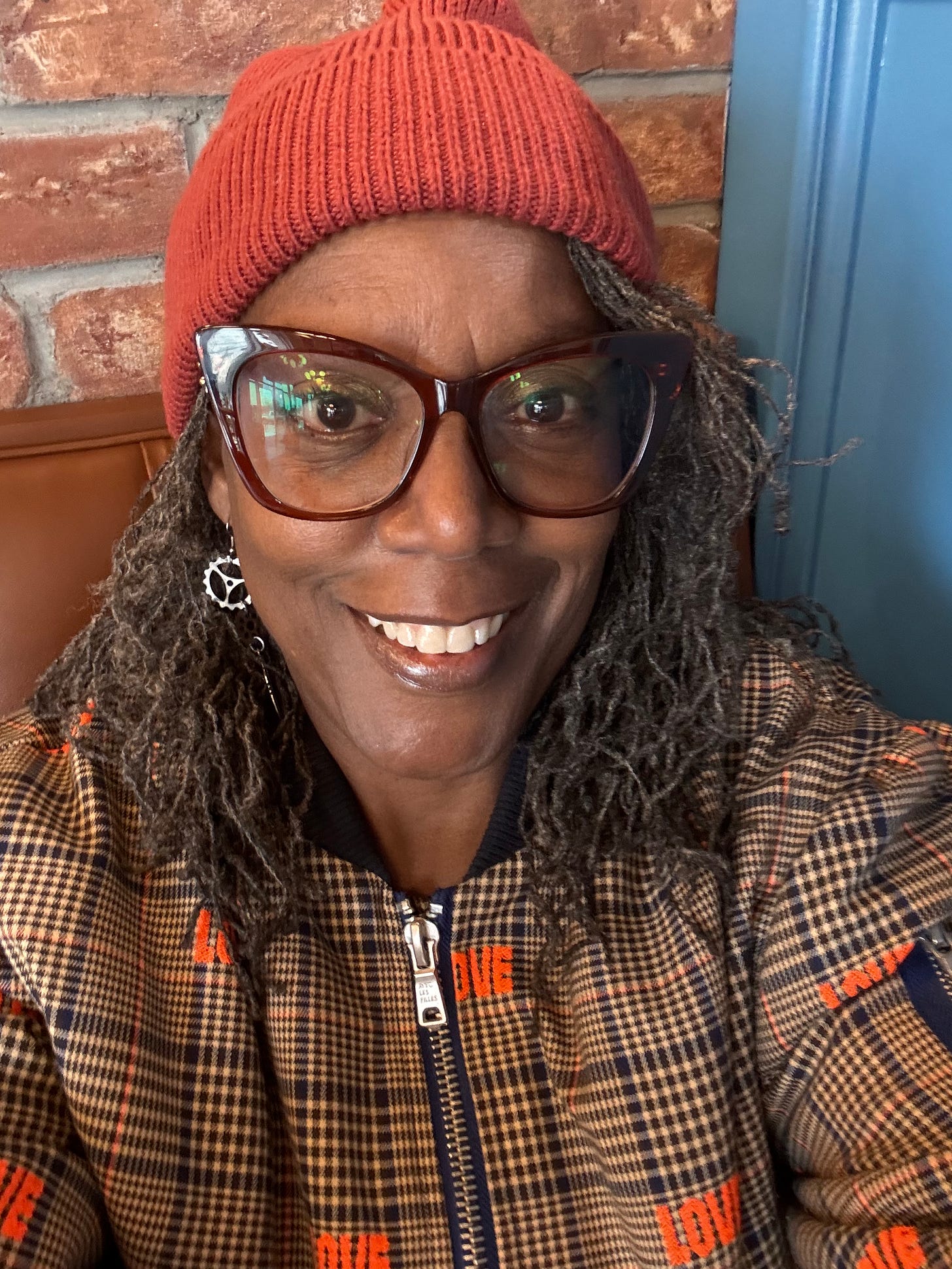

Photograph by Link to Photographer, Lis Anna

New Wings Glenis Redmond I am a daughter of the dust. I am a true sister of the yam. I come from a long line of serious brown women that don’t take no mess or apologize for living. I am birth from the morning earth deep, rich and free. My middle name Gale describes how I move in this world sometimes gracefully other times stormy. Glenis, welsh for valley. I have dwelt there far too long. I am a raven I am a crow. I am a nappy bat. I am a mosquito. Call me anything black that has wings and flies.

Thank you

Thank you for writing and sharing what white people do not know or maybe even believe life is and always has been in this country. The woman who raised my brothers and me endured so much including the murder of her son. And then was back at work the next Monday. Still she loved us. I don't know if she imagined how much my brothers and I loved her, but I understand that would never heal what had been done to her.